November 09, 2023

Founded by Joe Bataan, Ghetto was a brief but groundbreaking Latin music label. Six of the Ghetto Records titles and one previously unreleased have been reissued by Now-Again Records.

On vinyl: Ghetto Records Collection

Ghetto Records was a way to get over on The Man and out of the ’hood, a bold move by an artist looking for independence and creative control in an industry that had exploited his talents and treated him like chattel.

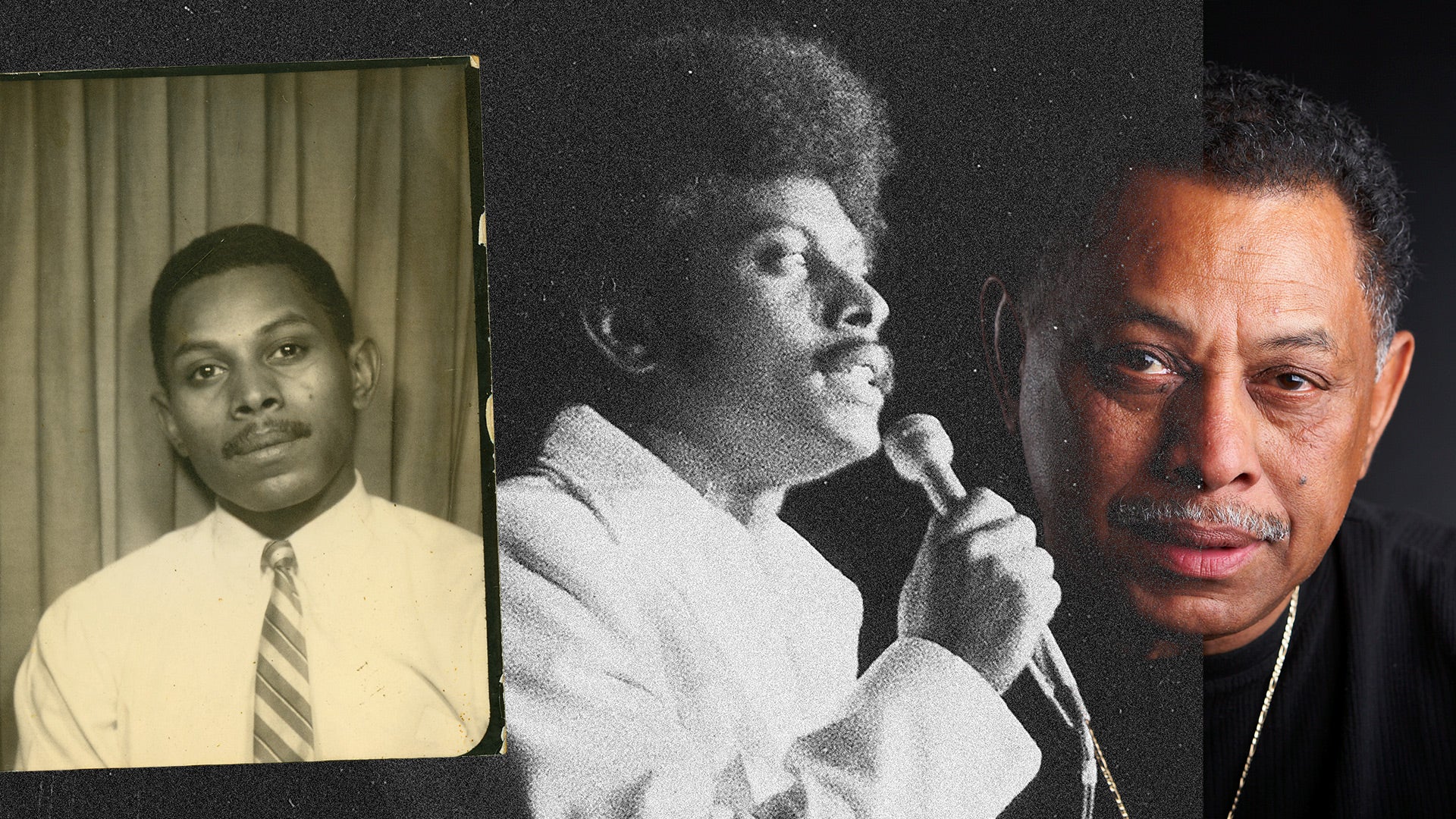

Joe Bataan, a self-described “Afro-Filipino mestizo soul preacher” and “professor with a degree in Street-ology,” is at the very center of our investigation into what happened to “the little Latin label that thought it could” because, without him, Ghetto Records would never have existed, and the catalog could never have been officially reissued. As Bataan puts it today, “Ghetto Records was part of my journey, a stepping stone to everything else that I’ve done. I learned enough that it enabled me to get out of the box with my thinking, it showed me how to deal with adversity.”

Like many dreams and schemes born of the street, this one was audacious, perhaps even reckless to a fault. Hatched from desperation, full of hope and chutzpah, Ghetto Records came crashing down shortly after its inception due to forces beyond Bataan’s control.

In the early 70s Bataan was in a period of intense conflict with Fania Records and its owners Jerry Masucci and Johnny Pacheco. When Bataan decided to walk away from the label he’d helped build––and that had made him a household name in the barrios of Nueva York––Masucci said nothing, giving him the cold shoulder. “The standoff almost destroyed Joe Bataan,” Bataan remembers, speaking in the third person. “But I was determined to go my own way. I didn’t know how hard it was going to be but I stuck it out because of my pride. I guess I was the first artist that really stood up to Fania. Masucci was surrounded by yes-men, even Héctor Lavoe, all of them guys. Don’t get me wrong, Ralfi was a good friend of mine, but he was never going to replace me. I was too embedded in New York at that time.”

Out in the cold––or “on the streets,” as he puts it––Bataan did what he could to survive, but he was always behind on his rent. While hustling to make ends meet, Bataan thought about what it would take to make it on his own without Fania. He figured that he’d learned enough about the record business from his Fania bosses that he could produce records himself. But, he says, “I didn’t have the follow-through, and that was the financial [backing]. I never had money.” Bataan’s return to the street hustle lasted almost three years, and Bataan admits he fell in with some unsavory characters from the underworld in a temporary return to the “negative way of life” he led before becoming a bandleader. “During that time, Fania Records were so upset [with me] that they instructed [influential Latin music radio DJs] ‘Symphony’ Sid [Torrin] and Dick ‘Ricardo’ [Sugar] not to play my records. They were going to destroy me.” Still under contract with Fania, Bataan decided he “was going to record something, no matter what––like Machiavelli says, by any means necessary.”

With the backing of George Febo, a shady character well known in the streets of Spanish Harlem, Bataan started Ghetto Records.

With Febo providing significant investment, the pair rented a small office in a commercial building at 850 7th Avenue, near Times Square and, ironically, Fania’s first location. Bataan would undertake the same musical and creative responsibilities Johnny Pacheco had fulfilled at Fania, while Febo would be Ghetto’s version of Jerry Masucci, running the office and keeping the books for their shared enterprise. However, this arrangement was short-lived; Bataan was slowly edged out of his creative position, with Febo taking over the entire direction of the label. Bataan says he was mistaken in trusting that, when he shared his knowledge of making records with Febo, who he describes as a “negative guy” who “knew nothing about music,” he would not be usurped. “That was my downfall for a long time in my career,” he remembers. “My wife always said, ‘You talk too much, you share everything you’re going to do before you even do it, and then before you know it, you’re left holding the bag!’ And that’s what happened, he started getting ideas, like all the people that shared in Joe Bataan’s journey.”

The vinyl reissues:

Ghetto Records’ master tapes were largely lost in the chaos of the label’s closure in the mid-70s. Alapatt and Pablo E. Yglesias (aka DJ Bongohead) sourced the cleanest copies of rare original vinyl, which mastering engineer Jason Bitner spliced, restored, and remastered. The exception was the Paul Ortiz album Los Que Son whose master tapes Bataan zealously guarded over the years, and which was cut in an all-analog transfer. The never-before-heard Bataan songs on Drug Story were found on a master tape in Spain decades after Bataan thought he had lost it forever.

Lacquers for all titles except for Drug Story were cut by Bernie Grundman at Bernie Grundman Mastering.

Album List:

• Ghetto Records Presents Eddie Lebron (1970)

• Papo Felix Meets Ray Rodriguez (1971)

• Paul Ortiz Y La Orquesta - Son Los Que Son (1971)

• La Fantastica - From Ear to Ear (1971)

• Joe Acosta - The Power of Love (1971)

• Candido Y Su Movimiento - Palos De Fuego (1972)

• Joe Bataan - Drug Story (recorded circa 1972)

Now-Again and Vinyl Me Please collaborated on a limited-edition Story of Ghetto Records box set in 2022.