December 20, 2018

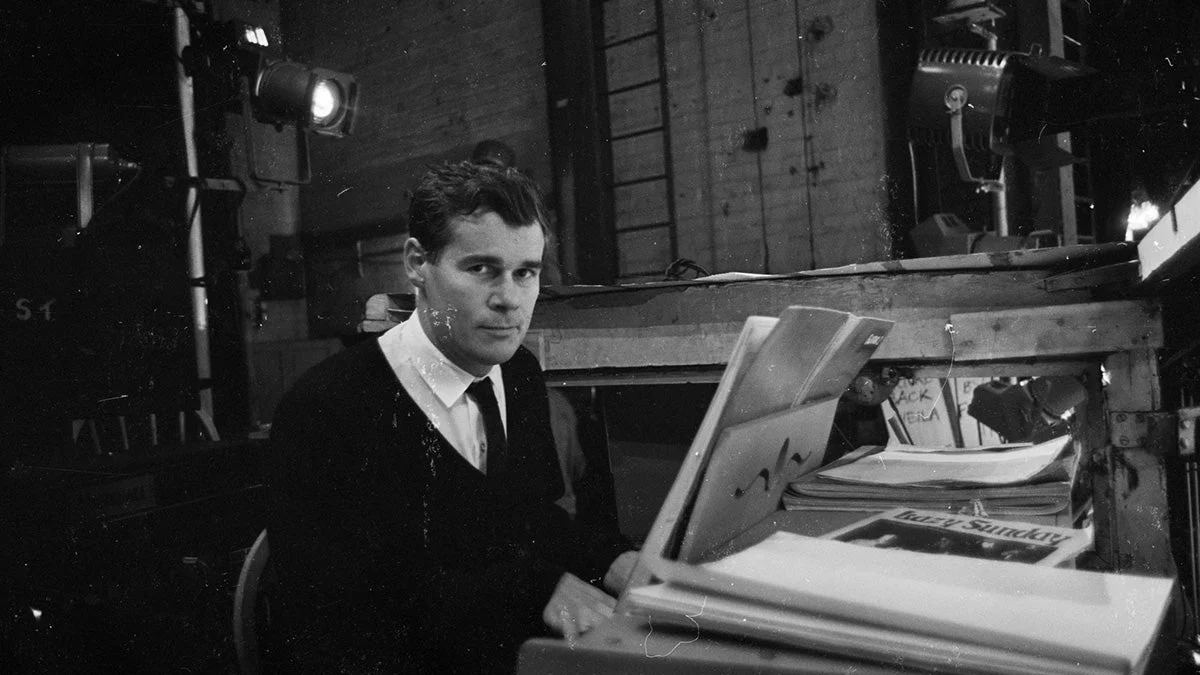

Composer, pianist and arranger Galt MacDermot died at 4 AM Eastern Standard Time on December 17th, 2018, a day shy of his 90th birthday.

While the cause of his death was undisclosed, he had been in failing health for some time. Here’s an essay on his life and influence by Eothen “Egon” Alapatt, who worked with MacDermot and his Kilmarnock label from the late-90s to the mid-2000s.

He was best known as the composer of the musical HAIR, a worldwide success, a crucible of the late 1960s, an indication that the counterculture had gone mainstream. And thus hit after hit from MacDermot’s pen made their ways around the world, from “Age of Aquarius” to “Let The Sunshine In.” These became indelible classics, at once of their time and beyond it. For MacDermot it was a happy, if unexpected, result of his talent and chance colliding, and while he loved the concept of theater, it was just an interesting stopping point in a lifelong musical journey. HAIR’s success was so unfathomable to him, he told me, that he first realized that his life had changed in an instance many of us would find mundane. While walking to his gig (he played in the musical’s pit band) on a rainy New York afternoon, he realized his feet were wet. He’d worn a hole in his sole – and for the first time in his memory, he walked into a shop and bought a new pair of his preferred Clark desert boots. I don’t know if we ever talked about financial success again except for how it could foster musical creation for those attuned enough to not be distracted by it.

Because, for MacDermot, what HAIR’s royalties bought him was the ability to do things on his own terms, to work with musicians he respected, and who respected him, as they recorded his ideas for issue on his own Kilmarnock Records. Kilmarnock’s founding predated HAIR– he’d issued albums such as The English Experience, an album by his warbly-vocaled alter ego Fergus MacRoy, and one of his masterpieces, 1966’s Shapes of Rhythm. That album contained the landmark performance of his “Coffee Cold,” a harbinger of everything to come in popular music. If only it had been heard more, like Lee Dorsey’s “Get Out Of My Life Woman,” James Brown’s “Cold Sweat,” or MacDermot’s HAIR hits. It would take thirty years for Shapes of Rhythm to see its due, when hip hop producers, searching for deeper sampling sources, tracked down MacDermot in his Staten Island home, a converted turn-of-the-century school house situated on an acre of land at the top of Victory Boulevard, across the street from Silver Lake Park.

FROM CANADA TO AFRICA

Galt Terence Arthur MacDermot was born on December 18, 1928 in Montreal, the son of Elizabeth Savage and Terence MacDermot, a Canadian diplomat. The elder MacDermot, a pianist, exposed his son to a variety of music at an early age. Through his father, young Galt heard opera and show music, classical pieces and swinging jazz, and he picked up the recorder at age five. By age eight he had adopted the violin, but it wasn’t until he landed behind the piano at age 14 that he realized music would be the center of his life. Nat “King” Cole and the infectious boogie-woogie sound emanating from the United States had hooked him. He took school seriously – and landed a BA in History and English from Bishop University – but he dedicated all of his spare time to his passion. His love for the great Duke Ellington grew and grew, and he became a self-described “jazz freak.” In 1950, when the Canadian government appointed his father High Commissioner to South Africa, he moved with his family to Cape Town and enrolled in a music program at the university there.

“The African Experience,” as MacDermot called his time spent in South Africa, would come to indelibly influence his musical development. His father, a progressive Jamaican native, hated the apartheid system propagated by the South African government. Thus MacDermot embraced the music created by black South Africans as he traversed Cape Town searching for music. He vividly recalled the drumming he heard in the city, freer than the jazz swing rhythm that he had grown accustomed to in North America. He recalled the complex singing that he came to recognize as the basis of American gospel. He recalled his family’s cook, a drummer who schooled him on ways to incorporate new beats into stock rhythmic phrases. And he recalled his summers spent in the North, listening to the work songs of African miners. Attempting to describe his experience, MacDermot told me “Once you hear African music, you…,” before he paused abruptly. He continued, “It’s serious music, they’re not faking anything.”

However, upon his return to Canada, MacDermot did not immediately put into practice that which his journey to Africa had taught him. He assumed the relatively low-key job of organist in a Baptist church and played with two bands on the side – one playing popular music at club gigs and one focusing on calypso. But it was in Canada that MacDermot would first break into the recording industry. He wrote some music for the play My Fur Lady in 1955 and ended up landing a record deal with the company that recorded the musical, Laurentien Records. In 1956 Laurentien recorded MacDermot’s Art Gallery Jazz, an LP that contained a version of a tune that he had written in Cape Town, “African Waltz.” In 1960 while en route to Amsterdam, he stopped in London to play his record to bandleader Johnny Dankworth. Dankworth told MacDermot that he would record the song, but at the time MacDermot thought little of it. It wasn’t until he heard from a friend that English radio was heavily rotating Dankworth’s cover that he realized he had his first hit. It was at this point that MacDermot decided to move to England, as he now jokes, “to exploit himself.”

THE ENGLISH EXPERIENCE

It didn’t prove easy. He lived on royalty checks for a time, and found some of his compositions recorded by other jazz musicians, like pianist Ken Jones. But he soon returned to Canada with a new mission. In England, he conceded that popular rhythm was changing from the jazz swing he’d grown up with to a straight 8 R&B/rock pattern. He would change with it. In England he had met writer Bill Dumaresq, another Canadian expatriate with whom he would collaborate often, until Dumaresq’s death in the 1980s. One of their first experiments was setting Dumaresq’s poem “Coffee Cold” to MacDermot’s solo piano, in 4/4 meter. “Coffee cold, brown and indifferent,” MacDermot sang, in one of the first examples of the complex, melancholic music he would create for the rest of his life. The song was cut to acetate, presumably as a demo for publishers, circa 1964, after he’d moved to New York City.

Julian “Cannonball” Adderly had covered “African Waltz” (and released an album under the same name) in 1961 and MacDermot had won a Grammy for his composition. His star was on the rise, and he met producer Rick Shorter, who at the time was in the business of assembling studio musicians to cut tunes for music publishers. Shorter introduced MacDermot to the mid-Manhattan studio musicians that would become his co-workers for the next few years. He met now legendary drummer Bernard Purdie, then a recent transplant from Maryland. He met bassist Jimmy Lewis, then emerging from a gig with King Curtis’s band. And he met “Snag” Napoleon Allen, an understated guitarist whose rhythm he found to be unmatched.

It was with these men that MacDermot cut Shapes of Rhythm, as he realized that he and his comrades were part and parcel of the rhythmic change he sensed would take over music worldwide. Shapes of Rhythmis an adventurous album, ranging from the raucous – influenced by rock, calypso and Cape Jazz – to the contemplative. It was in the latter category that MacDermot’s performances are the most prescient. “Coffee Cold,” performed on the album as an instrumental, is propelled by Purdie’s drums which, for the first time, deliver an iteration of the beat that would change the world’s rhythm as much as any beat played by Clyde Stubblefield or John Bonham or Zigaboo Modeliste.

MacDermot credited Purdie and his bandmates on Shapes of Rhythm’s jacket which, like all albums on Kilmarock, he financed and, as best he could, distributed. Kilmarnock would never be a money-maker, but MacDermot used it to inscribe his best ideas to vinyl. He would record ceaselessly in this period, often cutting acetates of his experiments with musicians who intrigued him, such as Jimmy Lewis’s friend, the drummer Idris Muhammad, with whom he recorded “Piano Concerto” in three parts in 1967. “I remember my father doing recording sessions when I was young,” his son Vincent reflected. “The sessions took all his energy. he wouldn’t do anything for days after, but when he had the tape, he would sit alone in the living room and play the music over and over, studying it.”

HAIR

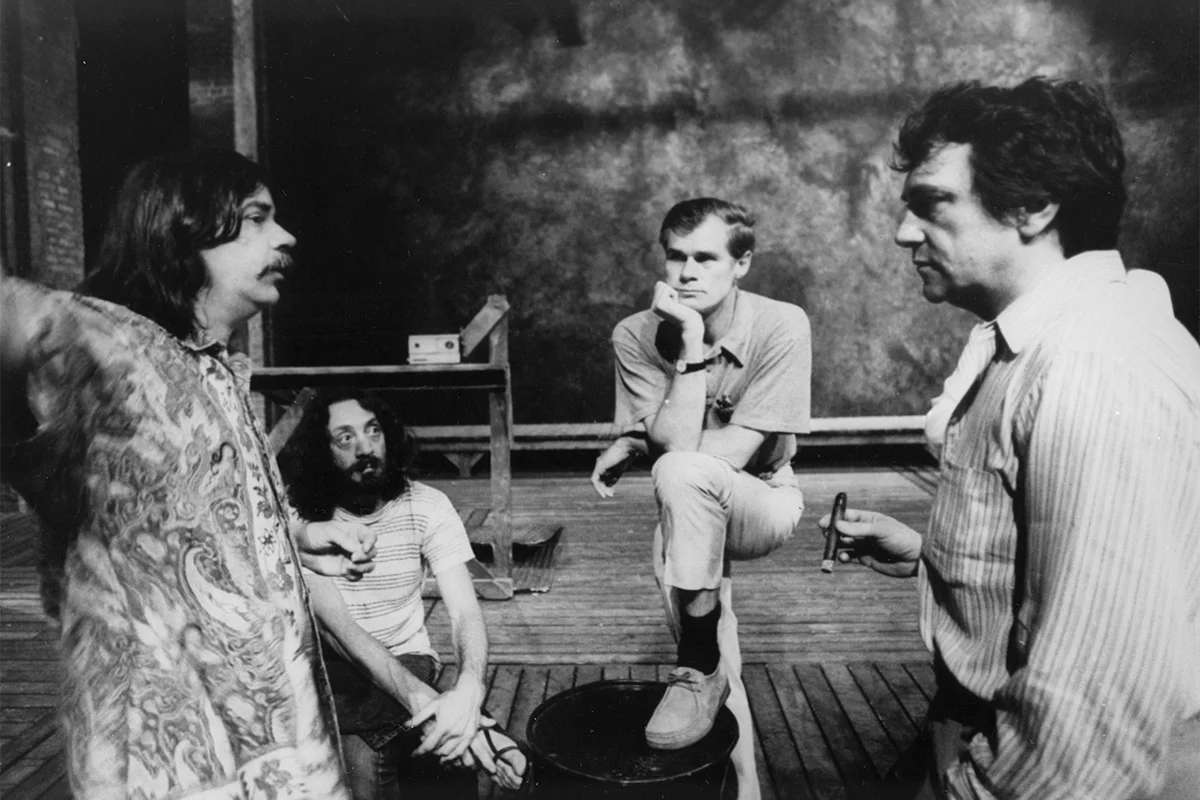

MacDermot met the jazz critic and music publisher Nat Shapiro around this time, and he told Shapiro that he was interested in writing another musical. Shapiro introduced him to Gerome Ragni and Jim Rado, actors who had just written a provocative play. They’d not thought of their play’s music, though, and Shapiro wouldn’t shop a half-baked idea. The three hit if off, and MacDermot scored the music to Ragni and Rado’s words in three weeks. Through Shapiro the trio shopped HAIR and eventually landed a deal with Joe Papp, an off-Broadway producer who opened the show at his Public Theater in the City’s Greenwich Village. The show ran a mere eight weeks and was moved to a Midtown club, The Cheetah, were it continued for another two months. It was nothing more than a fluke that Michael Butler – scion of a wealthy Chicago family who planned to run for senate on an anti-war platform – caught a glimpse of the musical’s RCA released album. The pink hued cover depicted a series of customarily dressed Native Americans and Butler, an enthusiast of this country’s first people, traveled to Midtown to see the show. He was taken by the play’s message – most strikingly its stance against the Vietnam War – and he arranged for a true Broadway opening. This was the break MacDermot needed. The play took off on Broadway, and MacDermot, who played with the show’s pit band for four months in New York, soon found himself traveling with Butler to Los Angeles, England, Montreal, France, Sweden and other faraway locations to oversee dozens of openings for the musical.

Vincent reflected on this moment in a moving eulogy he delivered at his father’s funeral:

“I have a sort of an image that perhaps [Rado and Ragni’s] words were like the point of the spear, that the force of my father’s music was always strong but the sharpness and the clarity of the words, the cleverness, the humor and fearlessness of HAIR, the definite decision on the part of the authors to disrupt the society they saw, all made this theatrical work have an impact in every city it was performed in.”

This, to me, is the crucial juncture in MacDermot’s life. When I first met him, and indeed for many years after, I had no vantage point for the landscape that unfolds around that level of musical success. Now I’ve seen it many times – those fortunate enough, through a fated combination of talent, luck, persistence and access, hit it big and then, more often than not, that’s it. They don’t ever create anything as important as their breakthrough, though a certain hype follows them for a time. Then the excitement of possible follow-up success – and the parasitic system that has surrounded them – dies, and those creators quickly become parodies of themselves, tied to something they come to loathe, yet are forced to revisit in an increasingly angular, downward spiral. In recent years, I’ve seen the victims of this type of musical ubiquity pop up as talking heads in documentaries, repeating worn sound bites about their weathered cultural touchstone.

This didn’t happen with Galt MacDermot. He brought his friends Jimmy Lewis and Idris Muhammad into HAIR’s band, and he spent 1968 developing his rapport with the ensemble, testing out rhythmic ideas with Muhammad and Purdie, alongside Lewis and guitarist Charlie Brown. He said no to big ideas foisted upon him by those wanting a slice of HAIR’s success as often as he said yes to those that seemed sincere – such as the impressionistic creation of the soundtrack to Martine Barrat’s film for Yves St. Laurent (which he issued on Kilmarnock as Woman is Sweeter) and one for a Stanley Donen picture, American Express, that never saw release. (MacDermot did keep a safety reel-to-reel of his psychedelic score; we later issued some tracks on his Up From The Basement anthology in 2001.) He was considered a rock composer, a mantle he begrudgingly accepted, if only because he tired of explaining what his music really was.

He and his closest musician pals were all steeped in the tradition of jazz and R&B and many were instrumental in the development of the music we now consider funk. But MacDermot wasn’t a funk musician and, though he had grown bored with jazz, he hadn’t tired of the genre’s best elements. MacDermot, like the greatest of the era, from David Axelrod to Serge Gainsbourg, created timeless music by consciously avoiding everything but what felt right to him. So his music took influence from the baroque, from Africa, from rock and from, mainly, the ideas his trusted friends brought into the studio when he brought them his ideas. MacDermot’s best from this era is minimal – his beautiful melodies ornamented only by the necessary rhythmic additions to keep a listener engaged to completion. A great MacDermot composition resolves itself in an odd way, leaving you feeling like you just said goodbye to a close friend. Its memory sticks with you long after the song has faded. You’re immediately ready to welcome it again.

INSTRUMENTAL MAGIC

As he entered the 1970s, MacDermot remained extremely active. He recorded an incredible instrumental album by the HAIR band for one of his only United Artists releases. And if the revolution he helped bring to Broadway was not enough, he also took place in a filmic revolution as well. He scored 1970s’s Cotton Comes To Harlem, one of the first Hollywood films to appeal to a black audience. The film, actor Ossie Davis’ directorial debut, helped usher in films that addressed the black American plight (see Melvin Van Peebles maverick Sweet Sweetback’s Badass Song, issued shortly thereafter) and MacDermot’s funky score hinted at the direction that composers like Isaac Hayes and Curtis Mayfield would adopt with their forays into the genre soon labeled Blaxploitation. He scored Two Gentlemen of Verona in 1971 and, while it wasn’t as big as HAIR, it was a hit, and he won a Tony Award.

He picked up projects as they appealed to him. Some, like the musical Dude he wrote with his HAIR collaborator Gerome Ragni, and an ill-fated space opera Via Galactica, flopped. But they always led to an album on Kilmarnock. As the 70s progressed, he left Broadway for good and recorded more instrumental music, as this was his first love. It was in this period that he started working with landmark studio musicians such as Ted Dunbar, Billy Butler, Billy Nichols and Wilbur “Bad” Bascomb, which led to albums like his Nucleus, a MacDermot masterwork.

From 1974 through 1978 MacDermot traveled extensively to Trinidad, working with acclaimed playwright and poet Sir Derek Walcott. This is not to say that he totally eschewed projects in the United States, as he composed the score to the a wild adaption of Eugene Ionesco’s Rhinoceros in 1975 and recorded a “Puerto Rican Soap Opera” with Pucho and his Latin Soul Brothers (including the legendary NYC funk musicians the Pazant Brothers) in 1976’s La Novela. But he searched for a new direction to take his music, something he would discover as he re-scored HAIR for its 1979 film release. Working heavily with string and horn arrangements – something he’d first tried with Rhinoceros – around Purdie, Bascomb and Brown’s rhythm section invigorated MacDermot, and he formed his New Pulse Jazz Band shortly thereafter. He often recorded the band for Kilmarnock, and gave a concert at Carnegie Hall annually in December to showcase that year’s ideas.

A REBIRTH THROUGH HIP-HOP

By the late 1980s, give or take a film score here and there, MacDermot had largely given up on the business aspect of the music business. But by the early 1990s, hip hop producers had discovered his major releases and his lawyer Stuart Prager started fielding sample clearance requests. “I had heard rap in the ‘80s – on the street you know – but I was never that impressed with it. It seemed like more of the same rhythms that I wasn’t interested in. Kind of tired funk,” MacDermot said. “But as producers started getting more adventurous with their beats, that’s when it changed.”

Though Howie Tee was the chronological first – with Special Ed’s “Ready To Attack” – Pete Rock was the first to seriously champion MacDermot’s compositions, first sampling Geoff Love’s version of “Where Do I Go” for “Can’t Front On Me” on his groundbreaking album Mecca and the Soul Brother, and then using the Broadway cast version as the basis for Run DMC’s “Down With The King.” Contemporaneously, Large Professor sampled the filtered bassline from the Japanese HAIR album’s “Dead End” for Nasty Nas’s debut, “Halftime.” Buckwild reached deeper, utilizing the instrumental of “Ripped Open By Metal Explosions” from the First Natural HAIR Bandalbum for New Jersey rappers Artifacts’ “C’mon with the Get Down.” And groups from Naughty by Nature to Masta Ace Inc. grabbed bits and pieces from MacDermot’s Cotton Comes to Harlem LP.

Enterprising New York rap producers and record collectors started journeying from the Bronx and Queens to Staten Island in search MacDermot’s Kilmarnock releases, and new sounds to sample. The first was Victor “V.I.C.” Padilla, then closely associated with The Beatnuts. During the recording of the vocals for The Beatnuts’ Intoxicated Demons EP in New Jersey, Padilla, a producer on the project, left the studio to go shopping in a Teaneck record store. After finding a copy of Tom Scott’s HAIR album, he asked the shop’s owner if he had other HAIR variations. No, came the reply, but one of his customers knew Galt MacDermot, HAIR’s composer, and he was accessible. And he had kept copies of the records that he’d pressed in the 1960s and 1970s. Padilla called, introduced himself, and MacDermot invited him to his home, beginning a mutually beneficial relationship. “Victor had an ear for certain chord progressions in my music that he liked – that I liked,” MacDermot told me. “He would spot them in my songs. I was more surprised of that than the fact that he had found me, or that he had heard about Kilmarnock.”

Padilla bought records and distributed them to collectors and producers in New York City, and MacDermot learned about hip hop through V.I.C. and the friends he brought with him, notably the Beatnuts’ JuJu and Buckwild’s Digging In The Crates associate Lord Finesse.

Producer Rashad Smith found a copy of Woman is Sweeter in his mother’s record collection. “My mother was in the performing arts, and collected everything of Galt’s as a fan,” he recalls. “I always remember her playing the album Woman is Sweeter– it stuck out to me. I then later started playing the album more frequently and heard parts that I could use.”

Smith found a quirky bridge in “Space,” which he looped and played to rapper Busta Rhymes, then emerging from his stint with Leaders of the New School. This became Rhymes’ breakout hit, 1996’s “Woo-Haa! Got You All In Check,” the anthem that established him as a superstar. Smith, then a Staten Island resident himself, sought MacDermot out and the two became friends. MacDermot had a tremendous respect for those that came to his door looking for a new path that started in the one he had trodden before, and he became an ardent listener of New York’s WQHT FM – Hot 97, then the nation’s most important rap station. “Hip hop saved the R&B feel – it gave another life to it,” he told me in the late 1990s. I found an old interview with him, from 1974, in which he said that rhythm in popular music had to change. By the late 1990s it hadn’t, and that perplexed MacDermot. “When I say rhythm has to change, maybe I’m being too forceful. Maybe it doesn’t have to change,” he reflected, in one of the many conversations we had on the subject. “You hear different rhythms come in and out, like the reggae rhythm came in for a while, and then the disco thing. I don’t know what’s in now – but I do know that the rappers are doing something serious. I’m really only interested in serious music. Pop music never meant a thing to me. Even when I was a kid dancing, I would try to get rid of the pop songs and put on Duke Ellington. You know, the good music.”

UP FROM THE BASEMENT

I cold-called Galt MacDermot in 1998, like those that had come before me, looking for copies of his Kilmarnock albums, specifically Shapes of Rhythm, which was already somewhat legendary in the East Coast record collecting community. Those copies were long gone, his daughter in law MaryAnne told me, but they had others they would send me if I’d play them on my radio show in Nashville. (At the time, I was a DJ on Vanderbilt University’s student-run radio station WRVU.) I’ll never forget when the package arrived and I heard “Duffer” from Nucleus. I became obsessed by the idea of what MacDermot music I hadn’t heard might sound like. I asked for a meeting. And I was told that, if I could make it on a Tuesday at 4 pm, I could meet Galt at a New Pulse Jazz Band rehearsal in a 34thStreet loft.

I was interning at Loud Records at the time, across town. It was supposed to be a gateway to a dream job, and I had pulled every string I could to get myself in, but I hated my time there. Steve Rifkind, the label’s founder and boss, showed up from time to time and people cowered. Accountants looked fussy and mean when they popped their heads out of their offices. Loud’s stars showed up, from Big Pun to Mobb Deep, but they didn’t look proud to be on the label, they looked angry. I spent my free time looking for records in Lower Manhattan’s vinyl haunts, and meeting those indie label folk that would have me, such as Raw Shack Records’ George Sulmers. There was an alterative to the hip-hop mainstream, it seemed, and the soundtrack was better. In George’s case, it involved a lot of Galt MacDermot albums. He showed me many Kilmarnock releases I’d not yet heard.

That day that I met Galt is ingrained deep in my psyche. He was serious yet kind. The musicians that surrounded him – Bernard Purdie, “Bad” Bascomb, his son Vincent – were happy to be in his presence. A joy filled the room as they played. It was just the exact opposite of being at Loud. I decided that I had to work for Galt MacDermot, though I didn’t know what that meant. A year later, Vincent offered me that job – I would organize the music in Galt’s home. I would spend the summer before my senior year in college in his legendary basement, surrounded by as much MacDermot music as I could handle. I hastily accepted, and was given the keys to a small apartment atop their garage, which I stayed in until I was able to rent a space in Brooklyn.

I set out to organize, first, all of MacDermot’s reel-to-reels, acetates and test presses. They were stacked everywhere, in his upstairs music room, next to his Eames lounge chair in the sitting room that housed his Steinway baby grand; in the adjacent sun-room where he did his daily composing. It was shocking, how much of his music had not yet been issued. And the best of the unissued music was stunning; the Hamlet acetate, the only surviving instrumentals from a Joe Papp production he’d scored in 1968, offered “Woe Is Me,” which was as great as “Coffee Cold” or “Space” – prime, morose MacDermot. I put together cassette tapes and listened endlessly to his music on my two hour commute each day.

There were dozens of copies of most of his Kilmarnock releases in the basement, hundreds of some. Not of Woman is Sweeter or Shapes of Rhythm; those were long gone. But there were enough that he would let me bring copies to New York producers as gifts. I was hungry to meet my heroes, and I did meet them, MacDermot wax in hand, from Salaam Remi to a visiting James Yancey, then known as Jay Dee.

I remember sitting in the office space we’d set up in MacDermot’s home and ringing Jay, to tell him I could send him a package of Kilmarnock music if he’d have it. He surprised me to tell me that he was actually in New York, working with Common. Did I want to come and deliver the music to him that evening? He’d be in a session with Bob Power.

That evening, I showed up. And time stopped. At least the session did, temporarily, as Dilla thumbed through the albums I’d brought, and Common and Power talked about HAIR, and we discussed these obscure, independent records that, at the time, were on their way to becoming part of hip hop’s sonic framework. I’ll never forget the grace I felt at that moment, as these master craftspeople took time to host me as an emissary for this elder whose music was yet to be fully understood. I felt like I’d found my path, and I felt grateful that MacDermot had made it possible. The next day I rushed back to Staten Island to tell MacDermot all about the experience. This was Jay Dee, the guy who remixed “Woo Hah,” who had produced The Pharcyde’s “Running.” He knew all about your music, and he was there with Common, one of the best rappers living. And Bob Power who gave us the speaker-busting The Low End Theory knew all about HAIR! I think it pleased MacDermot, to know how much I cared, how excited I was, that I was trying anything I could to spread his musical gospel. But that wasn’t as important as what was often the topic of the day: where was music going, who was pushing it there, and how. In that moment, we somehow addressed all of those things at once.

In the coming years, I would help MacDermot and Vincent reissue some of Kilmarnock’s landmark albums and compile MacDermot’s unreleased music in a series of anthologies. With Count Bass D, I hosted an event in Nashville in 2000 where MacDermot, Purdie and Bascomb headlined a hip hop-heavy line up. Everyone in attendance was floored by their performance. Mr. Dibbs, the groundbreaking Cincinnati turntablist, wouldn’t have seemed to the casual observer like a MacDermot acolyte, but he was. He has since recalled the event:

“He played a solo during ‘Let the Sunshine In.’ I went to stand up but was stuck in my chair. I couldn’t get out of it, the chain attached to my wallet was stuck. I looked up and Galt smiled like he could see that I wasn’t able to move. Then everything went away. Everything. There was just that music and a long series of flashbacks. It was the most calming feeling I ever felt, except for when I died.

When I was walking up to Galt to say how incredible the show was he turned to me, looked me in the eyes and said, ‘did you enjoy the solo?’ I said it was mind blowing. Then he took his index finger and pushed it into my forehead and said ‘it will always live in there.’”

Yes, that’s right. The most calming feeling he ever felt, except for when he died. Dibbs clinically died, twice. (He’s doing just fine now.) I tried to get him to explain more about how those moments could compare to that moment with MacDermot but, other than affirming that it was true, he really couldn’t explain it any better.

AND NOW WE MASH

When I moved to Los Angeles to work for Stones Throw Records, I continued working for Kilmarnock, and ferrying MacDermot’s music around the world. Madlib had sampled Cotton Comes To Harlem and a cover of “Where Do I Go” on his Quasimoto album The Unseen. His brother, Oh No, agreed to produce an entire album around the Kilmarnock catalog. MacDermot visited LA from time to time, and I often returned to the East Coast, where I would take the Staten Island Ferry over to visit him, eat the cucumber sandwiches that his loving, deeply devoted wife Marlene prepared, and take a stab at the perennial MacDermot question – when would popular rhythm change again, how would it change, and why?

Of course we never answered the question, but it was a fun enough exercise. And the best of the best – DOOM, Madlib and Jay Dee, now J Dilla – were listening to MacDermot’s music and crafting their own responses. When Dilla gave me the master for his album Donuts, and I listened to it in my car on the way back to Stones Throw’s Eastside Los Angeles office, I heard his “Mash,” a masterful flip of MacDermot’s Nucleus song “Golden Apples Part II.” I thought back to a conversation MacDermot and I had, nearly a decade before, when I had asked him about the innate musical sense possessed by the best hip- hop producers and what it meant, specifically, for his musical legacy.

“It’s excellent. It’s nice that people are ready to hear this music. I recorded so much music, and if people didn’t feel it, then I filed it away. Even people like my old managers weren’t interested,” he had told me. “But now there’s interest – and that’s a whole lot better than no interest. I like the appreciation – the fact that these young guys hear what I heard.